SPARC: Innovative magnet technology to accelerate the timeline for fusion

SPARC fusion reactor aims to demonstrate net fusion gain by 2025 through innovative magnet technology

Originally published in Felix (https://felixonline.co.uk/)

In September 2021, researchers at MIT spin-off Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) reached a major milestone in their ambitious plan to build a fusion reactor capable of net energy gain by 2025. The demonstration of the high-temperature semiconducting magnets, with a field strength of 12 tesla, is a key technology hurdle for the team. These magnets are at the heart of their proposed design, which if successful, pave the way for the construction of the first fusion power plant by 2030.

Fusion reactors have long been identified as a highly desirable energy source. First, they have a small environmental impact, using small land footprints and small quantities of fuel to operate, without emitting greenhouse gases. Additionally, they provide a consistent controlled source of power, independent of the weather or the hours long startup time of fission reactors. They are inherently safe, incapable of the runaway chain reactions and disasterous accidents of fission reactors. Finally, while they do produce some radioactive waste, this radioactivity will decay to safe levels on a timescale of decades, rather than millennia, making the waste far easier to dispose of.

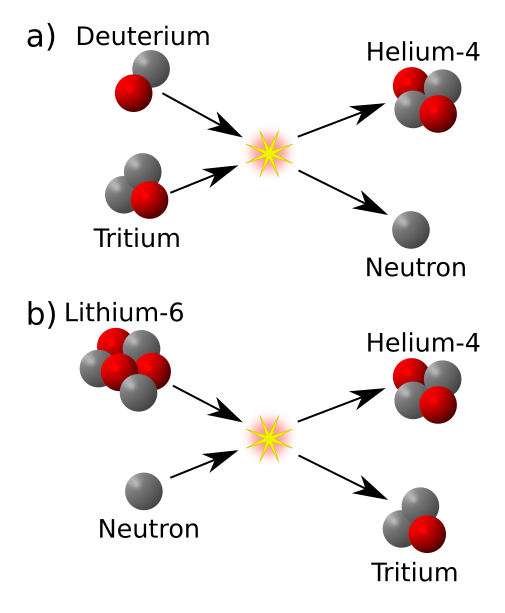

Figure 1: a) Fusion of deuterium and tritium to form helium-4 and an energetic neutron. b) Absorption of a neutron by lithium-6 to form helium-4 and tritium. Fusion reactors operate via the fusion of the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium, which releases energy. Deuterium (D) nuclei possess one proton and one neutron, while tritium nuclei possess one proton and two neutrons. Deuterium is found naturally in low concentrations in Earth's oceans, bound with hydrogen to form heavy water (D2O). It can be extracted through established industrial processes. However, the natural abundance of tritium is too low to allow for practical extraction methods, so most tritium is produced industrially through the irradiation of Lithium-6 with energetic neutrons in nuclear reactors - a process referred to as tritium breeding. While currently performed in fission reactors, new fusion reactor designs like SPARC aim to allow fusion reactors to take over tritium production.

However, fusion energy generation faces a host of complex problems. One such problem is the physics of controlling the plasma, which is at a temperature of 100 million °C. This high temperature is required in order to ensure that the deuterium and tritium nuclei - which make up the reactor’s fuel - have enough energy to fuse; it also means that they move at extremely high speeds. A magnetic field can be used in order to contain these fast moving plasma particles. However, the motion of the charged particles within the plasma, combined with their complex electric and magnetic interactions, leads to the development of waves within the plasma. This can disrupt the shape of the plasma, stopping fusion or causing the plasma to hit the reator walls.

The high magnetic field planned for the new reactor - called SPARC - is hoped to make this problem easier, by allowing for the plasma to be confined within a much smaller volume and suppressing the waves which arise as the plasma is compressed.

The stronger magnetic field is only possible due to the recent innovation in superconducting magnet technology. Previous designs for tokamak type fusion reactors – a common reactor design which uses magnetic fields to contain and compress the plasma – use low-temperature superconducting materials, such as niobium-tin (Nb3Sn). These materials limit the strength of field achievable, thus requiring that the fusion reactor be made larger in order to reach net energy production. A larger reactor inevitably leads to higher costs and long construction times, such as those experienced by the ITER reactor in France, under construction since 2007.

SPARC instead uses rare-earth barium copper oxide (REBCO), a high-temperature superconductor capable of achieving twice the maximum field strength compared to niobium-tin. This is commercially available in the form of a steel and copper backed super conducting “tape”, which can be wound in order to form a magnet of the desired shape. REBCO has only become a viable option in recent years, as it has become possible to manufacture the necessary quantities at an economic price.

Innovation in the magnet design will also help SPARC and its successor ARC to overcome the tricky problem of containing the neutron radiation from the fusion reaction. Conventionally this is done using a neutron blanket, which consists of hundreds of panels made from neutron stopping materials. These panels require complex cooling systems to remove the heat deposited by the emitted neutrons and must be assembled with absolutely no gaps, so as to prevent radiation escaping and damaging the outer components. These plasma facing components degrade far more quickly than the rest of the reactor, likely requiring that they be replaced yearly in a commercial reactor. Conventional neutron blankets must be disassembled piece by piece, passing the pieces through the cramped space between the electromagnets so as to achieve this. The cost and complexity of this is so high that many critics see it as the killer flaw of fusion as potential power source.

SPARC proposes to replace this labour intensive assembly with a single component vacuum chamber, which will be immersed in a tank of the molten salt FLiBe – containing Fluorine, Lithium and Beryllium – at a temperature of over 460 °C. The liquid FLiBe serves double duty, as both the neutron absorber and cooling fluid, which can be pumped through a heat exchanger in order to remove heat from the reaction vessel. There is only one problem: how to replace the tank and vacuum chamber when they are intertwined with the superconducting magnets like links on a chain? CFS’s novel solution is to split the magnets into two sections, joined together by superconducting jumpers, which can be rapidly disassembled to allow the entire inner section to be lifted in or out of the reactor.

The choice of FLiBe also carries another advantage. As the FLiBe absorbs neutrons, some of the lithium atoms will be converted to the hydrogen isotope tritium, the rarer of the nuclear fuels used in the reactor. This process would allow the reactor to produce more tritium that it consumes, reducing the cost of producing fuel for the reactor.

It is through this combination of technological innovations in reactors’ magnets, cooling and radiation shielding that Commonwealth Fusion Systems hopes to rapidly drive down the cost of nuclear fusion, bringing it into the realm of commercial viability.

Prof. Dennis Whyte's talk on YouTube is a great jumping off point for more information on the reactor and Commonwealth Fusion Systems.