Massive Gravity

How allocating mass to gravitons could help explain the expansion rate of the universe

Originally published in Felix (https://felixonline.co.uk/)

From cosmology to quantum mechanics, the theory of massive gravity seeks to answer a fundamental mystery about the expansion of the universe by weakening the force of gravity itself. Recently joining Imperial College, Professor Andrew Tolley – one of the authors responsible for the theory’s inception – presented his work as part of the Imperial Inaugurals lecture series.

At the Limits of Current Physics

The rate of expansion of the universe poses a major mystery to physics. It was first confirmed in 1998 that not only is the universe expanding, but that this expansion is accelerating over time. The expansion of the universe – along with the consequential regression of distant galaxies – was first predicted in 1927 by Georges Lemaître, based upon his work on Einstein’s equations of general relativity. This remarkable prediction was confirmed just 2 years later by Edwin Hubble, marking the start of decades of research into the rate of this expansion.

Initial expectations were that the rate of dispersion of galaxies would slow over time due to the gravitational attraction between them. Thus, when it was observed that the expansion of the universe was accelerating, this required a new explanation. The source of this acceleration has been dubbed “dark energy”. This is a feature of space itself, which creates a gravitational field with a repulsive effect. This field is proportional to the energy density of dark energy. Since this energy density is constant – and therefore doesn’t become diluted as the universe expands – this causes the expansion rate to be constant, i.e., the time it takes the universe to double in size doesn’t change.

It has been proposed that this phenomenon could be accounted for by vacuum fluctuations, a quantum mechanical phenomena whereby particle-antiparticle pairs may be created and annihilated within empty space, provided that the two particles exist for a short enough period of time. However, all attempts to estimate the contribution from vacuum fluctuations obtain an energy density value which is far too large compared to that expect based on the observed rate of expansion.

Implications of a Massive Graviton

The physicists behind massive gravity have conceived of an approach to resolving this conundrum. They propose that one of the assumptions implied by general relativity – that gravitational fields are conveyed by massless carrier particles called gravitons – is wrong. In general relativity, the strength of gravitational attraction falls as the inverse square of the distance. This effect is due purely to geometry, as the gravitational effect of a mass must be spread out over a spherical cross section, whose area increases with the square of the distance.

Imbuing the graviton with a mass would change this relationship, causing gravity to lose strength with distance faster than the inverse square relationship. Importantly, it would mitigate the impact of the hypothesised high energy density of vacuum fluctuations, by reducing their repulsive gravitational influence on distant matter.

The Ghost Problem

Most modifications to general relativity which introduce a graviton mass also introduce the possibility of a particle with negative kinetic energy – called a “ghost”. Tolley explains that this is a “disastrous” result as it “allows the production of an arbitrary number of positive and negative energy particle [pairs]”. Avoiding this posed a major obstacle to a theory of massive gravity.

Tolley and his colleagues Justin Khoury and Claudia de Rham had originally come up with a ghost-free gravitational model where the force of gravity leaked into higher spatial dimensions, consequently weakening it at large distances. However, this model with 6 spatial dimensions was very difficult to analyse. The trio noted that from the perspective of a 3D observer in their model, the graviton was no longer a massless particle.

Supposedly, it was impossible to move back to a 3D model but somehow preserve this graviton mass. Two previously published papers had proven no-go theorems, which stated that any attempt to construct a 3-dimensional massive theory of gravity would invoke the presence of ghosts.

It was only when researchers Gregory Gabadadze and subsequently Claudia de Rham identified errors in the no-go theories previously published that the possibility of constructing a theory of massive gravity in only 3 spatial dimensions came back under consideration. Shortly thereafter followed the team’s breakthrough, taking only a matter of weeks.

Experimental Predictions

The ultimate test of massive gravity lies in whether it agrees with experiment. Various predictions of the theory stand to be tested by ongoing or future experiments. These predictions include implications for the precise motion of planets, star systems and galaxies – including within our own solar system.

Massive gravity also influences the nature of gravitational waves. If the graviton is massive, gravitational waves must travel slower than the speed of light. Additionally, massive gravity predicts the existence of additional gravitational wave polarisations, giving a total of 5, compared to the 2 predicted by general relativity.

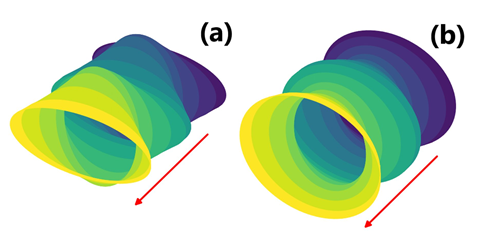

Polarisation describes the way in which the waves displace particles as they move through space. General relativity only permits this motion to occur perpendicular to the direction of the travel of the wave, with the particles following an oscillating elliptical pattern (a). In massive gravity, additional modes of motion are possible, including particles oscillating in a circular pattern (b) or oscillating parallel to the direction of motion.

Figure 1: Motion of a ring of particles due to the passage of a gravitational wave. Red arrow indicates direction of travel of the gravitational wave.

Much of the experimental evidence will come from gravitational wave detectors, such as the current largest ground-based detectors, LIGO and VIRGO. It will likely take decades until we obtain conclusive evidence as to the validity of massive gravity. However, this won’t halt the work of the theorists, as they continue to search for viable models to explain the mysterious accelerating expansion of our universe.