Fighting Habit Relapse

Recently, I’ve caught myself out for trying to use my phone as an emotional crutch.

I’d keep checking my phone, swapping between my different social apps checking for (nonexistent) new messages. It was supposed to be a behaviour I’d corrected months ago. I’d trained myself to check my phone less, disabled notifications for most apps and blocked certain websites. Yet here I was, anxiously checking my phone for no reason at all. I had relapsed into an old bad habit.

This leads me to ask: What leads us to relapse in old bad habits? How can we combat the phenomena of habit relapse?

Old Coping Mechanisms

A few weeks ago, I experienced a period where I felt usually anxious and unmotivated. I struggled to identify a cause initially, dismissing the feelings when the came up as isolated variations.

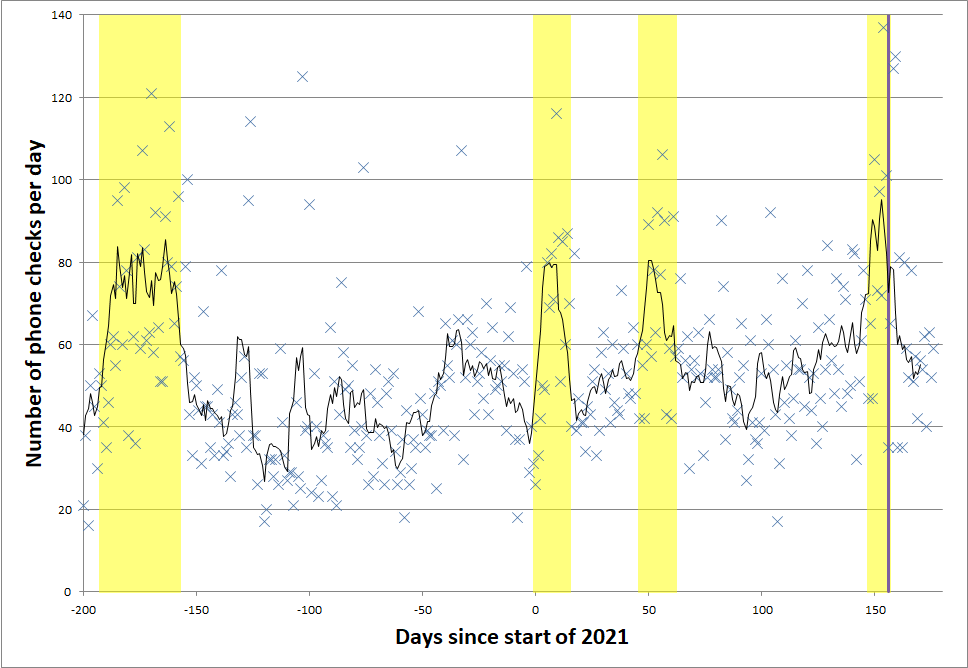

Eventually, I started to notice my compulsive phone checking and pulled the data on my phone usage. This revealed a clear trend: once every month or two, I’d have a spike in my phone usage, brought on by something which make me anxious or stressed.

Figure 1: Number of times I’ve checked my phone, black line is a 7 day running average, vertical purple line is the date this story is set.

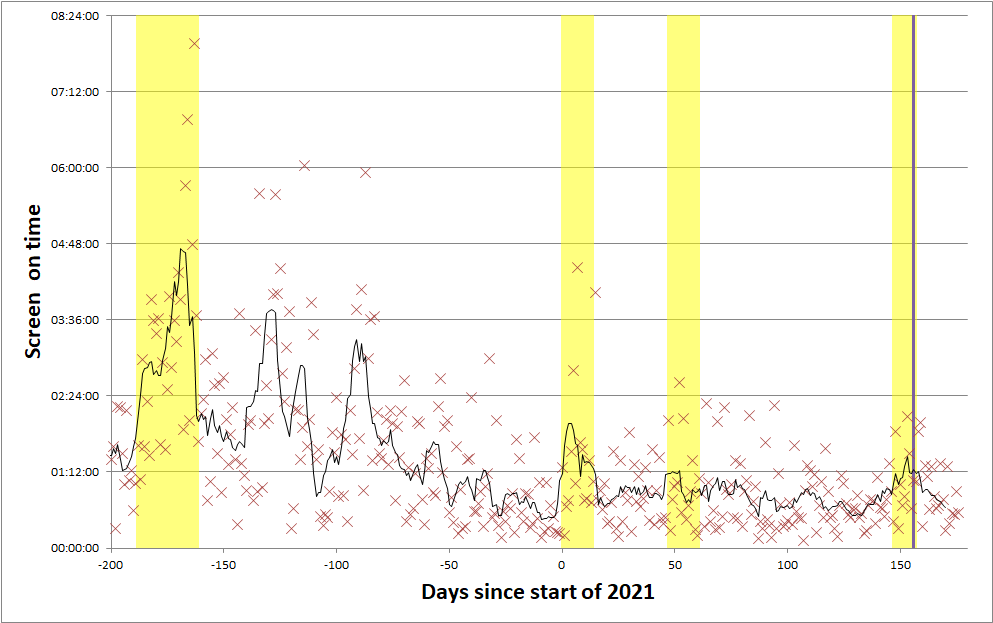

This phenomena wasn’t new to me, as I’d taken concerted effort a few months ago to cut down my phone screen time. I’d deleted apps and games, blocked YouTube and news sites and practiced keeping my phone off my person.

The data supports that these measures were effective. Plotted below is my daily phone screen on time. While spikes in my phone usage used to include massive increases in screen time, now it’s only the number of times I check my phone which rises dramatically. I didn’t even notice two of the spikes in phone usage until I looked at this plot, as the change in checking my phone was comparatively small.

Figure 2: My phone screen on time, black line is 7 day running average, vertical purple line is the date of this story.

Stress Canary

All these plots are very nice, by why does any of this data matter?

It matters, because by noticing my elevated phone usage, I was able to take action to control my behaviour, in turn directly reducing my anxiety and improving my motivation for other activities. My phone usage was not only a clear signal of my disturbed state, but a key contributing factor.

Let my explain. My behaviour in checking my phone was compulsive, that is to say I would pick up my phone and start checking it before I even became aware of what I was doing. Because, of previous positive associations with the phone, I would use it as a source to seek quick reward, even if this was mostly futile.

When I noticed my intent-lacking phone checking behaviour, I took steps to stop it. I started to put my phone on the other side of the room, I deleted my email apps and I changed the display to be black and white for a while. However, I also noticed that I needed to change my behaviour more broadly, as my phone usage wasn’t the only area where I had become undisciplined. I’d also stopped exercising regularly in the morning, removing distractions while I worked and even brushing my teeth consistently.

In this sense, my spike in phone checking acted as an early warning that my habit were slipping and needed attention.

Cycles of Improvement

Returning to figure 2, it’s notable that the spikes in phone screen time become smaller and smaller over time. This indicates that while I would relapse into a bad habit, I gradually brought this under control over time, getting better at stopping it sooner on each occasion. In sum, I’ve become better at managing my habits.

I think this is important to remember, as when trying to improve a bad habit or start a good habit, its so easy to start beating ourselves up the moment that we slip up. However, the goal isn’t to get better today, its to be better in a year’s time.

In-fact, one might view the cycles of slip ups and re-correction as a natural part of the process, after all we pay more attention to a habit when the consequences of failing to maintain it / prevent it are fresh in our mind. However, eventually it must become routine, almost subconscious, which means we must run the risk of falling out of it sometimes.

In this context, improvement means being able to pick yourself up and get back into a disciplined state faster than you did last time.